Up South

Most Americans have a shallow knowledge of the civil rights movement, demonstrating a dismissive, naïve and inaccurate perception, which trivializes the economic, moral and physical atrocities embedded in our communities. This lack of attention and information leads us to breathe the recirculated air of a resurgent racial and ethnic division, hurting everyone -- black, white or brown -- AGAIN.

To combat the racism that impacts housing, education and health as a systemic source of inequality, organizations such as the Washington Regional Association of Grantmakers (WRAG) and Leadership Greater Washington (LGW) seek to expand the depth and understanding of philanthropic and civic leaders. Racism is an underlying obstruction that stalls the implementation of government and private programs to ameliorate poverty, inequity and hopelessness in our region.

You may already be familiar with LGW, as several of our senior staff are members, including Joe Budszynski, who previously served as its board chair. WRAG is an association of more than 100 of the most well-respected foundations and corporate giving programs in the Washington D.C. region. WRAG’s Putting Racism on the Table learning series educates funders on the many aspects of racism, including structural racism, white privilege and implicit bias. LGW and WRAG jointly sponsored a Civil Rights Learning Journey to Memphis, Mississippi and Alabama.

The Putting Racism on the Table series underscored the importance of understanding the history of race in America. The trip was an opportunity to build a deeper understanding of the movement for civil rights and racial justice. Over the course of four days, we visited museums and houses of worship that played significant roles in the activism of the 1960s. We also visited sites of key protests, murders and graves. We met individuals who were leaders on the ground in the 1960s and people who are still working for change today.

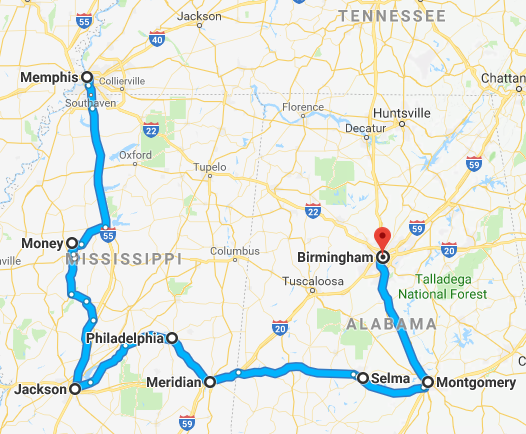

After flying into Memphis, where Martin Luther King was murdered at the Lorraine Motel while in town to support a protest of black trash collectors, we rode a bus through cotton fields and small towns. We ended our trip in Birmingham, Ala., which was known as “Bombingham.” Between 1947 and 1965, there were over 50 dynamite explosions in the city that were used by Ku Klux Klan members and sympathizers to suppress the black community's quest to end racial segregation and acquire the right to vote. Even riding the bus was a notable experience. We watched the movie Selma as well as a documentary, Neshoba. Philadelphia, Miss. was the seat of Neshoba County where three civil rights workers were tortured and murdered. Two of them were white, one had just arrived from New York the day before he was killed. Former civil rights workers rode the bus with us. They shared their experiences and pointed out significant sites along the way. They spent time in jail, witnessed violence and hatred. Many seem to suffer from moral injury because of the battle scars to their bodies, minds and souls. Many of the civil rights veterans now in their 60s and 70s were as young as 15 when they marched for their right to vote and right to humanity.

See the map of our bus route.

It rained every day, the muggy weather was thick, the wilting heat was interminable and the mosquitoes dive bombed with precision. Still, I would take this journey again. It was a stunning charge to continue the work for racial justice and peace.

The people on the trip were the very best travel companions. They were serious about learning, kind to each other and able to communicate through the anguish, shock and shame. The group was almost evenly split between people of color and white people.

Members of our group were mostly philanthropists and executives from foundations. They were phenomenal learning partners because of their authenticity, sensitivity and willingness to talk about what we were seeing and feeling. We had facilitators to help debrief and wrestle with our emotions.

For many of my fellow travelers, this was their first trip to the Deep South. Some, both black and white, expressed apprehension about traveling through the South. I found this incomprehensible coming from people who live below the Mason Dixon line in former slave ports in Virginia and Maryland. Cities around the Chesapeake Bay were second only to Charleston and Savannah as arrival ports for the slave trade. In 1642, the first slaves were brought to St. Mary’s City, Md. Slaves arrived in Virginia in 1619. Virginia was home to the capital of the confederacy during the Civil War. The Charlottesville march of neo-Nazi’s and Klan members took place in Virginia last year. A “neo-confederate” is running for senate on the Republican ticket in Virginia. A leader of the alt-right white nationalist movement and his “think tank” on white supremacy moved to King Street in Old Town Alexandria a little over a year ago.

Those of us from the Deep South call this region “Up South.” Up South characterizes people from northern states who harbor racism and believe in white supremacy as much, if not more, than the Deep South. Many try to cloister racism against black, brown, Asian and Native Americans to the southern states but it has permeated the entire country. Racism is alive and active everywhere.

A recent example of Up South is Vermont, the whitest state in the country and so far north it borders Canada. On Sept. 27, 2018, many newspapers including the Washington Post and The New York Times posted articles about Vermont’s only black female lawmaker who resigned after facing years of racially motivated attacks online, as well as "home invasions," vandalism and Nazi swastikas placed on trees around her property.

Diversity, equity and inclusion are hard work. It has to be intentional. It starts with learning and acknowledging how we got here and why racism is so persistent. Hugging, sharing food or having people of different races in your family does not absolve anyone of racism. It is not enough, not nearly enough. Naïve platitudes such as “let’s all just love each other” insults and trivializes the actual organizational and personal work that has to be done.

The Civil Rights Learning Journey illuminated the parallels between then and now.

Still, the struggle continues.

Group on stairs of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

Jatrice Martel Gaiter will be posting a series of photos and blogs about her Civil Rights Learning Journey.